The data genie is good and real from the bottle.

The rise of data consulting firms, the rise of public data sharing websites, and the rise of data usage in the media (ahem, ahem) all show how important statistics are to how we perceive and analyze the game.

Knowledge sharing has been a key catalyst for the creation and development of many metrics and statistical models. However, the curtain that every football fan wants to peer behind is the use of analytics at professional clubs. It is understandable that these internal data departments will maintain a high level of confidentiality in order to maintain a competitive advantage over rivals, but what does this situation look like?

The “Moneyball” approach remains a buzzword to explain the data-driven methods adopted by clubs like Brentford, Brighton & Hove Albion and Liverpool. But any club that has found success with data knows it’s not as simple as Oakland. As baseball CEO Brad Pitt snaps his fingers and points at numbers, Jonah Hill’s guy in Moneyball.

Analytics departments need to focus their energy wisely. The simplicity of the message conveyed by Dr Ian Graham, Liverpool’s research director until 2023, was notable at the 2021 StatsBomb conference when he declared that “recruiting and retaining players is the most important job – ten times bigger”.

Engagement is also key. You can have the best statistical models and machine learning algorithms in the world, but aligning and integrating that work with key decision-makers is where the impact of analytics can be maximised at club level.

Brighton owner/chairman Tony Bloom ensures the club’s staff benefit from data provided by his company Starlizard, which has helped lesser-known players become Premier League stars including Kaoru Mitoma, Moises Caicedo, Alexis Mac Allister and Julio Enciso.

Similarly, his Brentford counterpart, Matthew Benham, is the founder of statistical research company Smartodds – a business designed primarily for professional gamblers but instrumental in helping Thomas Frank’s team find value in the player recruitment market.

If the club’s owners or sporting directors are less data-oriented, there can often be a communication gap between analysts and decision-makers. Recently, companies such as Soccerment and SentientSports have used Generative AI will help bring this together by distilling complex statistical analysis into simple football language. — think ChatGPT for player searches — but challenges can still exist.

“Best practices in analytics are not about creating the most “complicated” model or algorithm, but analyses that are trusted and accepted by decision makers, which ultimately has an impact “about your processes,” says Dan Pelchen, founder of analytics firm Traits Insights. “Trust and understanding can help more experts use data on a daily basis, helping to avoid bias and reduce risk.”

There has been a lot of commentary in recent years about the growing world of football analytics, but — in addition to a recent research paper published in April — there has rarely been an objective, statistical description of the data ecosystems within individual leagues.

Traits Insights has gathered information on around 500 members of staff from over 90 clubs in the top four divisions of English football – split across data analysts (a general statistics-based role), recruitment analysts, first-team analysts (for example, performance/technique/opposition analysis) and general analytics managers – to better understand the challenges clubs face in creating ‘best practice’ analytics processes that Athletic Now you can share exclusively.

Identifying best practices is one thing, but implementing them is another thing entirely.

Establishing a coherent, self-sufficient analytics function requires significant investment from management, and making a business case for its long-term viability can be difficult.

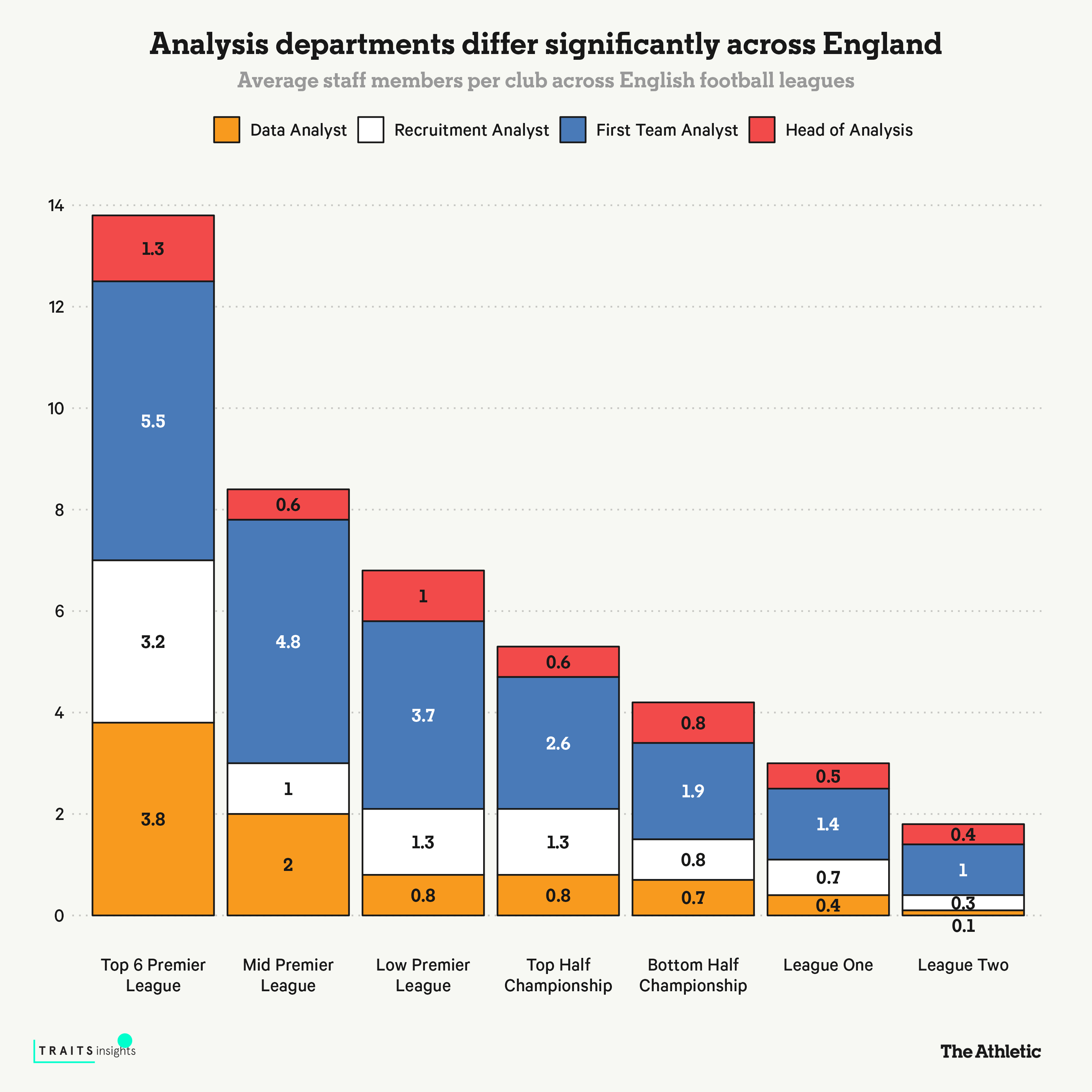

Traits Insights analysis found that the ‘traditional’ top six Premier League clubs (Manchester City, Arsenal, Liverpool, Manchester United, Tottenham Hotspur and Chelsea) employ an average of around 14 members of staff, which is twice the average among clubs in the bottom half of the same league.

Not surprisingly, these numbers drop as you move down into the Championship, League One and League Two, the fourth tier of football in England.

For some, staffing constraints may mean that some analysts will often be required to play a mix of “handyman” roles—for example, a data engineer (collecting and managing large data sets), a data analyst (interpreting information and presenting it to colleagues), and a data scientist (building statistical models to provide insights) in one role.

“Data analytics is still a relatively new area within clubs,” said one data scientist at a Premier League club, who spoke anonymously to protect the relationship. “People with varying experience are often enthusiastic about incorporating data into their workflows, but a club typically starts by diving in with a small investment—for example, one junior data scientist position and one data provider subscription.

“Those making this initial investment typically don’t have a background in data and are understandably unfamiliar with the different skill sets required of data scientists, data analysts, and engineers. When the first junior hire starts, they can quickly become overwhelmed by demands that can’t be met without a framework that enables rapid and meaningful insights.

“This can quickly lead to frustration on both sides. It’s no coincidence that the clubs with the most successful data departments have people at the top who come from quantitative backgrounds.”

A similar opinion is shared by everyone working in English football.

“A good data engineer is key to productivity and enabling other roles to succeed. It’s often the hardest role to fill and is often overlooked because it’s not glaring or particularly visible to everyday practitioners,” said a data scientist at EFLalso speaking anonymously to protect relationships“Data scientists are primarily responsible for generating models and delivering those insights, while data scientists have the most human contact—they are responsible for developing tools and delivering clear visualizations and presentations.

“Each of these three roles has specific responsibilities and skills that are essential to fulfilling their roles. Without one, the others would face increasing challenges. If a team member leaves, all of our skill sets are considered the same, when in fact they are completely different disciplines.”

The desire to use analytics has grown exponentially in recent years. However, it’s important to remember that specialist knowledge is required to manage and interpret data, build statistical models, and create interfaces (such as dashboards and visualizations) that enable other members of the club to understand the analysis.

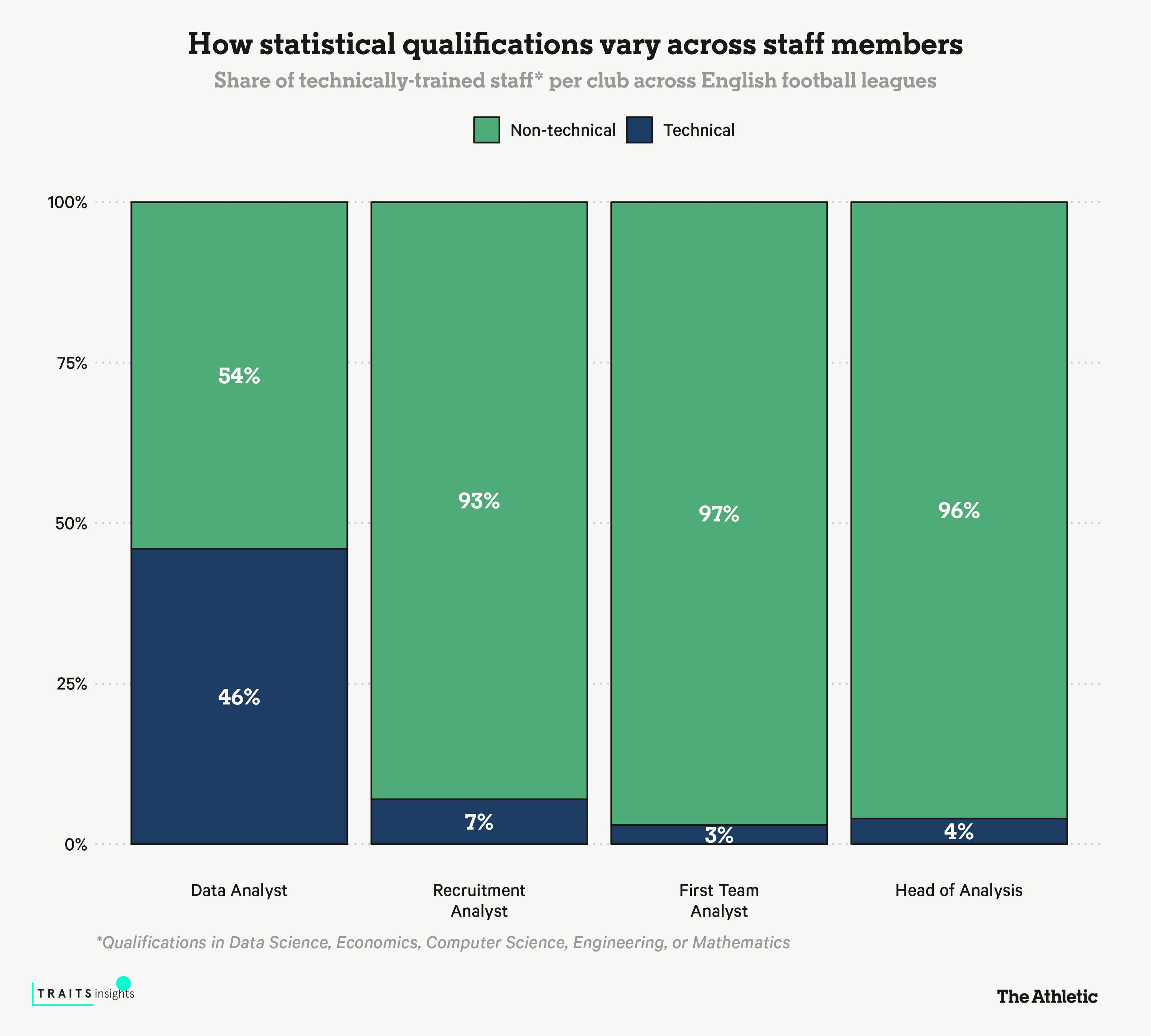

This requires specialized education and technical training to create such advanced models (such as neural networks and machine learning algorithms) — drawn from sciences such as data science, economics, computer science, engineering, and mathematics.

Many staff members have qualifications in sports and exercise science, performance analysis or similar areas – which require a great deal of technical training – but statistics qualifications among staff are rare in football. The Traits Insights analysis found that 46% of data scientists in the sample had a technical background in statistics, while about five% of other analytics staff had such a background.

Limited support staff with expertise in data and statistical analysis can be a burden on individuals when building technical systems internally. The key objective is for all team members to be able to develop such systems and draw insights across the club’s ‘production line’ of workflow – from junior data scientists to senior staff, including sporting directors.

Around 75 per cent of the 20 Premier League clubs have dedicated data analysts, with 50 per cent having multiples. By comparison, only half of the 24 Championship clubs have a dedicated data analyst, with the number similarly decreasing as it reaches the 24 teams in both League One (25 per cent) and League Two (less than 10 per cent).

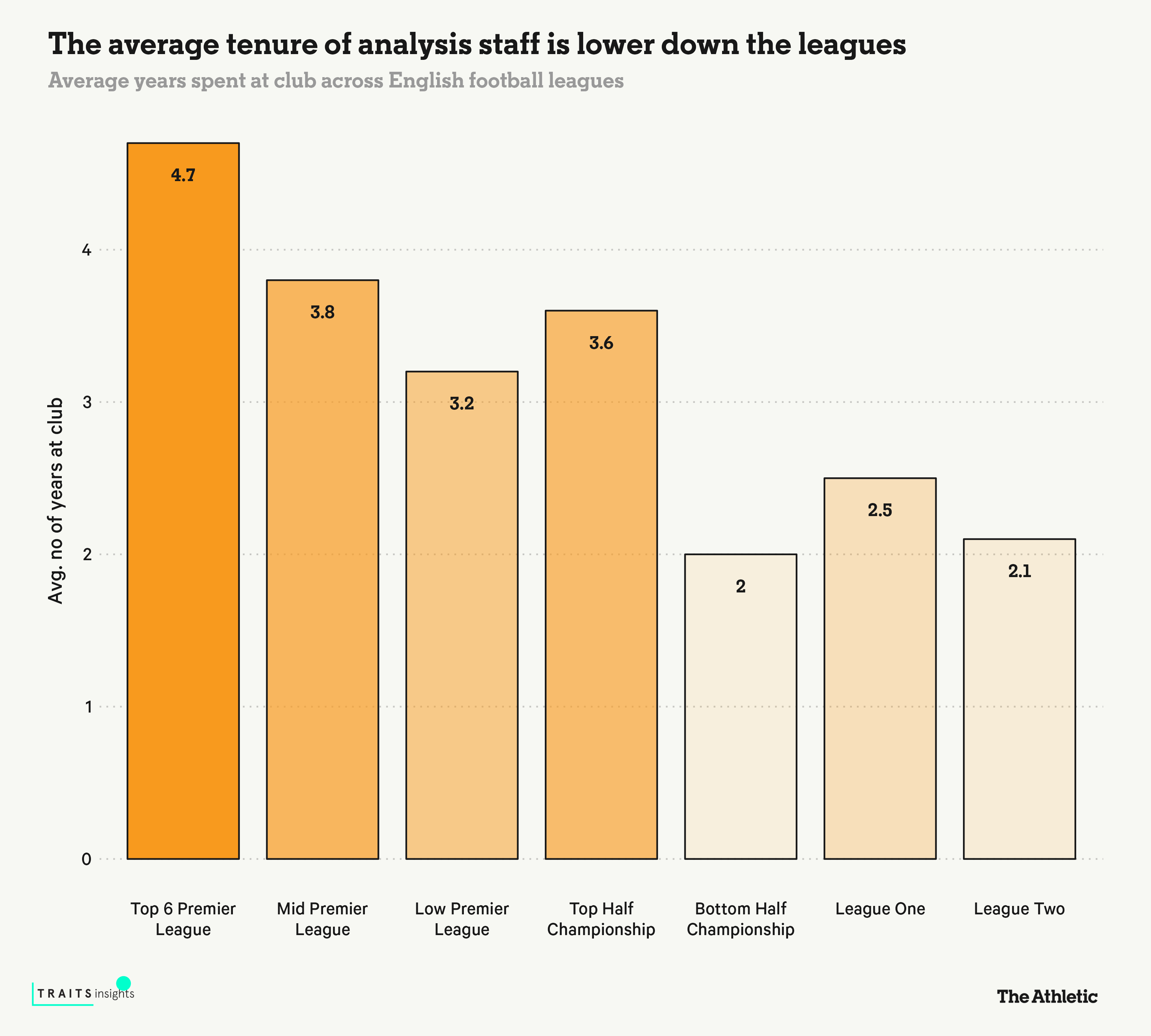

As cliché as it may be, football is a results-based business. Sporting directors often have a long-term vision for a club, but that is not always the case as you go down the three tiers of the Football League.

For support staff, having time to build statistical models and generate tangible insights is easier said than done. In clubs with higher turnover of coaching staff, these workflows and systems can naturally break down if a new manager or head coach has a different method of doing things. If this happens, it could hinder the development of the analytics department.

Similarly, analysts working for lower league teams may want to work for other clubs and move up the league table, increasing the likelihood of staff turnover at lower levels of the hierarchy. This was reflected in Traits Insights analysis, which found that analysts working for the Premier League’s top six teams had an average tenure of 4.7 years, compared with 2.5 years or less in League One and League Two.

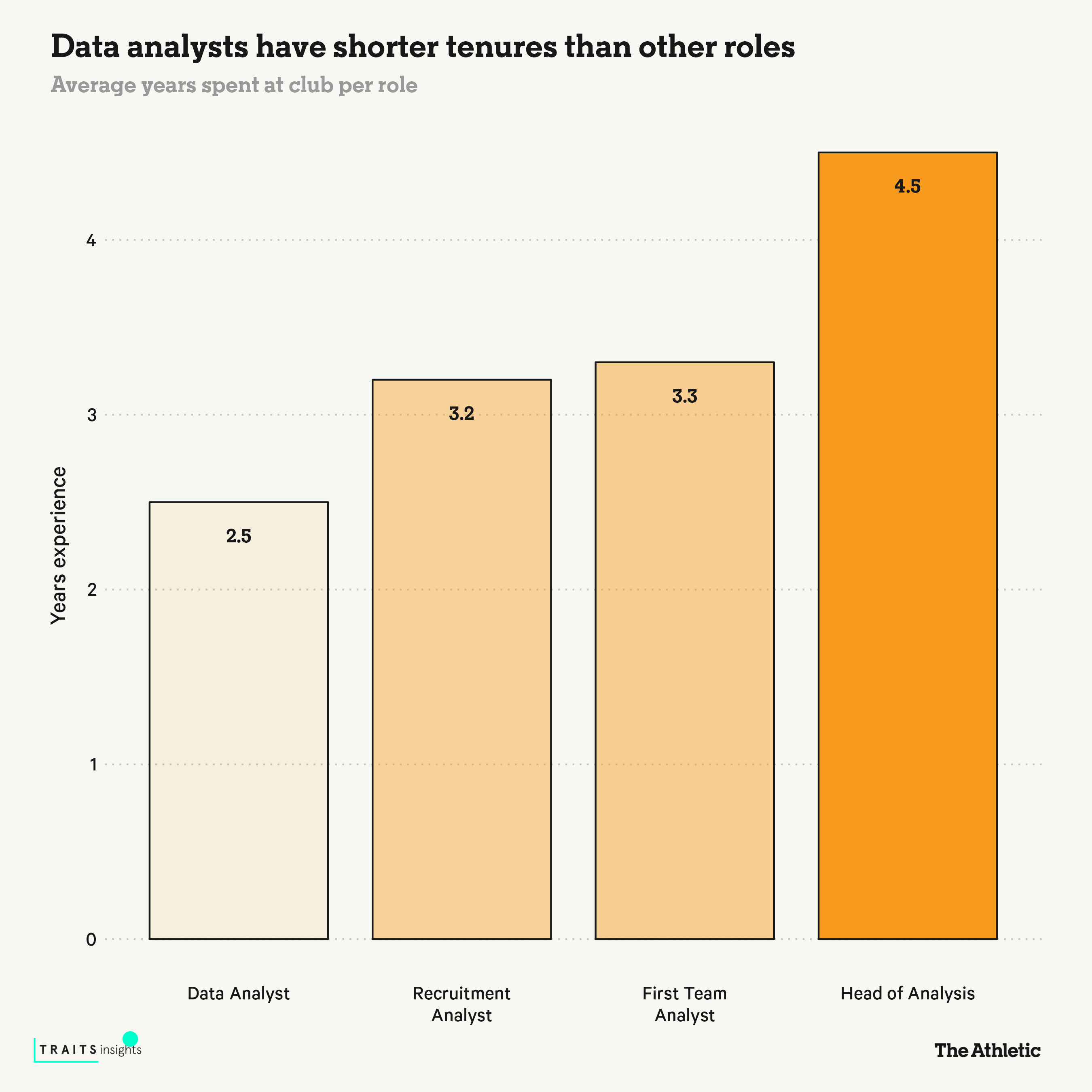

Broken down by role, the club’s head of analytics tends to be in the role for the longest period. Interestingly, data analysts have been in their roles with the team for 2.5 years, which speaks to the early days and potential transience of the job compared to other support staff at the club.

“These results are not surprising when you think about how new data is to football, and also how valuable these skills are to other industries,” said a Premier League data scientist, quoted earlier in this article.

“In clubs, the data analyst role often starts as a junior role, but the skill set required at a club is more in line with a senior role in other industries. If you can meet all the requirements to work at a club, you will be in high demand outside of football, so it’s understandable why people might move up more quickly than they would into other roles.”

When it comes to building an analytics department, there is no single path to success, nor is there a set method for clubs to develop their infrastructure. Best practice is hard to achieve without stability, strong technical skills and investment – and the complexity of such work means the Moneyball method is often idealised beyond reality.

Of course, clubs with bigger budgets can invest more in their analytics departments, but data analytics can be most effective when it comes to work that impacts player recruitment, retention and talent development, and establishing clear lines of communication between departments is key.

Whether you outsource the work to an external consulting firm or build your own data team within your club, there are still plenty of opportunities to gain a competitive advantage – at every level of the game.

(Top photo: Nick Potts/PA Images via Getty Images)

#data #departments #evolved #spread #English #football #clubs